Chapter 4. Levels of text representation

Version 3.0 (12 December 2019)

by Haraldur Bernharðsson and Odd Einar Haugen

4.1 Introduction

The electronic transcription of a manuscript text aims to accurately reproduce the text with a standardised set of characters. Such transcriptions can obviously never replicate every detail of the different shapes of the handwritten letter forms, their varying sizes or differing character and line spacing; a certain degree of standardisation is inevitable. The level of accuracy and attention to detail may, however, vary considerably from one edition to the next, as there is no single standard of transcription that can be applied to all editions of all medieval texts. One may perhaps, as in phonetics, refer to a spectrum between a broad transcription encoding only the most important elements of the text (speech) and a narrow transcription recording minute details.

For the purposes of transcribing medieval Norse texts, three different levels of transcription may be defined:

- A facsimile level (<me:facs>): A letter-by-letter transcription with a selection of palaeographic characteristics and the retention of abbreviations as in the manuscript.

- A diplomatic level (<me:dipl>): A letter-by-letter transcription with a small selection of palaeographic features and the expansion and identification of abbreviations.

- A normalised level (<me:norm>): A transcription in normalised orthography.

The choice of level of transcription ultimately depends on the aims of the edition and the needs of the intended readership. For some, a single-level transcription will be sufficient while others may prefer to combine two or even three levels.

The following discussion of these three different levels of transcription is not intended to be a firm standard that will fit all projects. Rather, these are guidelines that can be used as an example or a model and adjusted to meet the needs of other projects. For each project, the editorial policy can be presented in the header.

The perspective in this chapter is firmly a West Nordic one, encompassing Old Icelandic and Old Norwegian. The range of characters and abbreviation symbols are far wider in West Nordic than in East Nordic, so we believe that East Nordic needs are abundantly covered in this chapter. In a few cases, however, there are peculiarities of East Nordic, and these will be addressed explicitly.

Finally, it should be pointed out that while a rendering of a text on the facsimile level uncontroversially can be called a transcription, and probably also on the diplomatic level, some scholars might argue that a normalised rendering is no longer a transcription, but should be regarded as a kind of edition. The view taken here is that there are aspects of interpretation on all three levels, only more so on the diplomatic and especially on the normalised level. For the sake of terminological consistency, in this chapter we will refer to renderings on all three levels as transcriptions.

4.2 The facsimile level

The principal aim of an electronic facsimile transcription is to encode as much information about the manuscript text as possible. This includes the encoding of a wide variety of palaeographic characteristics (allographic variation), different types of abbreviation and punctuation, as well as information about the page layout (the mis-en-page). It should be stated emphatically that an electronic facsimile transcription is not intended to be – and can never be – a substitute for an image of the manuscript. The main value of an electronic facsimile transcription is the searchability afforded by the electronic encoding. An electronic facsimile transcription is thus not mainly intended to produce an accurate edition of the text for reading, but more a medium to encode electronically detailed information about the script, orthography, and layout as a tool for further research. The electronic transcription is thus essentially a data base that enables the researcher to extract information about the text. For palaeographic research, an accurate electronic facsimile transcription can thus be a useful complement to images of the manuscript, allowing the researcher to locate instances of particular characters or create frequency lists, to mention but two examples.

There are, of course, limits to how accurately the script can be reproduced in a facsimile transcription, and some normalisation of the allographic variation in the manuscript is inevitable. It is impossible to produce a single set of guidelines in this regard that will suit all the different projects. The accuracy of the transcription will depend on the aims of the transcription, and, not least, the script, scribe, and the date of the manuscript.

In a typical facsimile transcription, the text would be accurately transcribed letter by letter, encoding the following properties:

- Selected palaeographical characteristics; for instance: “ı”, “ẏ”, “ꝼ”, “ꝛ”, “ꝺ”, “ꞇ”, and “ƶ” (on which see more below)

- Abbreviations; for instance: “ꝼᷓ”, “v͛a”, “ħ”, “” (on which see more below)

- Different forms of punctuation

- Unclear readings

- Erased and/or corrected text

- Initials and litterae notabiliores

- Headings

- Line beginnings

- Column beginnings

- Page beginnings

In most facsimile transcriptions it would seem appropriate to reproduce the distinction of “r” and the rotunda “ꝛ”, the round “s” and the long “ſ”, as well as the distinction between the Half-Uncial “d”, the Uncial “ꝺ”, and the “ð”, “v” and the Insular “ꝩ”, the Caroline “f” and the Insular “ꝼ”, as shown in the table below along with a few other distinctions. Similarly, most editors would distinguish between some of the main variants of the most common abbreviation symbols, such as the “⁊” (&et;) and “” (&etslash;) varieties of the ok abbreviation, the ◌͛ (&er;) and ◌ (&ercurl;) varieties of the er abbreviation or ◌ᷓ (&ra;) vs. ◌ (&rabar;) for ra, ar or va. The reproduction of the Insular “ꝼ” and the flat-topped “ꞇ” has practical application in the transcription, as they can accommodate a superscript abbreviation symbol.

| Manuscript | Facsimile transcription |

|---|---|

| d ꝺ ð | d ꝺ ð |

| e | e |

| f ꝼ | f ꝼ |

| m | m |

| r ꝛ | r ꝛ |

| s ſ | s ſ |

| t ꞇ | t ꞇ |

| v ꝩ | v ꝩ |

| ⁊ | ⁊ |

| ◌͛ ◌ | ◌͛ ◌ |

| ◌ᷓ ◌ | ◌ᷓ ◌ |

Depending on the aims of the transcription, the editor may choose to go a step further and distinguish between, for instance, the principal variants of the letter “a”, the different types of the Insular “f”, or reproduce elongated descending final minims of the letters “m” and “n”, as shown in the table below with several additional contrasts. This will result in a more detailed transcription of the text, but it will never be free of normalisation, as the script will doubtless include, for instance, several subtypes of the two-bowl variety of the Insular “f” that cannot be accurately reproduced.

It is, of course, an editorial decision which of these contrasts to include. It should be kept in mind that the inclusion of more contrasts will slow down the transcription work and may increase the danger of inconsistency; this must therefore be carefully weighed against the aims of the project and the practicalities of carrying out the transcription.

| Manuscript | Facsimile transcription |

|---|---|

| | a |

| ꝼ | ꝼ |

| g ɡ | g |

| h | h |

| k | k |

| m | m |

| n | n |

| r ꞅ | r |

| z ƶ | z |

In addition, there is a multitude of finer details that cannot be produced accurately in a facsimile transcription, even if they are significant for scribal identification and dating of the script. These include, for instance, curves and loops on ascenders and descenders, fusions and bitings. A transcription with particular emphasis on palaeographic detail could be encoded separately on a palaeographic level: <me:pal>.

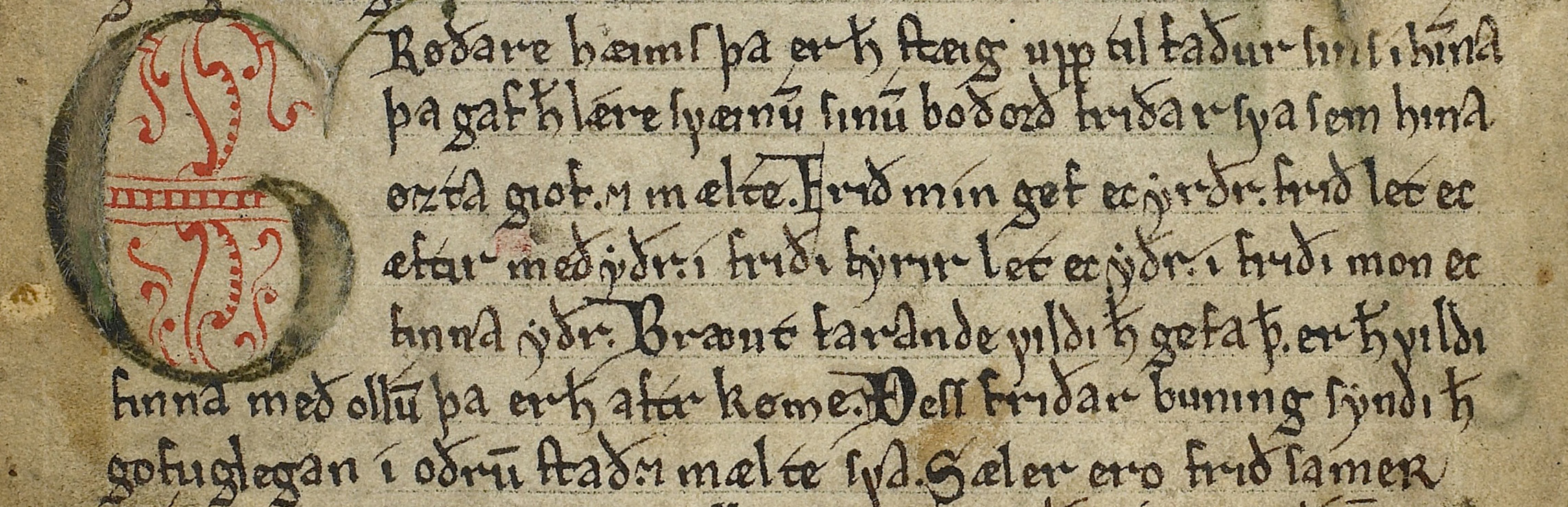

A short extract from an Old Icelandic manuscript, AM 233 a fol (mid 14th century) may serve as an example of a facsimile transcription:

Ill. 4.1. Niðrstigningar saga, an Old Norse translation of the apocryphal Evangelium Nicodemi. AM 233a fol, 28v, l. 1–2.

On the facsimile level, the text is transcribed character by character, line by line. Allographic variation is to a great extent reflected in the transcription, and abbreviation marks are copied without any expansion. If the transcriber prefers to use entities for all characters outside Basic Latin, the transcription of the text in ill. 4.1 would look like this:

&drot;&osup;ttin&bar; vá&rscapdot; bau&drot; michaele ho&fins;&dsup; engli.

at &fins;ylg&ra; a&drot;am ok &aolig;llu&bar; helgu&bar; ħs at lei&drot;a

þa i &pbardes;a&drot;i&slong;um hína &fins;ornu.and displayed (subject to an appropriate font) as

ꝺ ͦꞇꞇın̄ vá bauꝺ mıchaele hoꝼᷘ englı. aꞇ

ꝼylgᷓ aꝺam ok ꜵllū

helgū ħs at

leıꝺa þa ı ꝑaꝺıſum hína ꝼornu.

At the facsimile level, the transcriber ought to encode the manuscript exactly as it reads, even if it contains obvious mistakes. Corrections can be made by inserting a note, or it can be left to the diplomatic or normalised level.

4.3 The diplomatic level

The principal aim of a diplomatic transcription is to produce a readable while accurate edition of the manuscript text. In a diplomatic transcription, the text is accurately transcribed letter by letter, as in a facsimile transcription, but increased readability is attained by (a) expanding abbreviations and (b) reducing the number of palaeographic contrasts vis-à-vis the facsimile transcription. A diplomatic transcription, as defined here, thus requires more editorial intervention than the facsimile transcription in the form of the interpretation of abbreviations and the normalisation of allographic variation. The resulting transcription will thus be more readable for the human eye than the facsimile transcription, which, as discussed above, is perhaps more intended for electronic data mining than reading.

The principal characteristics of a typical diplomatic transcription as compared to a facsimile transcription are as follows:

- Abbreviations are expanded, and the expansions are identified (within <ex> elements); for example

- ꝼᷓ → fra

- v͛a → vera

- ħ → hann

- → ok

- Fewer palaeographic contrasts than in the facsimile transcription.

In deciding which palaeographic contrasts to retain, priority is typically granted to contrasts that have – or may potentially have – phonological value (represent phonological contrast in the language), although this varies considerably from one edition to the next. In earlier print editions, the availability of non-standard characters in the type set also often played a significant role.

The contrast between the Caroline “f” and the Insular “ꝼ”, for example, has no phonological basis; it is purely a feature of the script. Even if retained in a facsimile transcription, it would not be part of a diplomatic transcription where the Insular “ꝼ” would be replaced by the standard Caroline “f”. Typically, a contrast between a non-standard symbol in terms of modern typefaces, such as “ꝼ”, and a standard symbol such as “f”, would be replaced with the standard symbol. Similarly, the contrast between “v” and the Insular “ꝩ” would be normalised as “v”; the distinction between the Half-Uncial “d” and the Uncial “ꝺ” would be rendered with “d” only, and the distinction of “r” and the rotunda “ꝛ” would be replaced by “r”, as shown in the table below. None of these distinction are manifestations of a phonological contrast; rather, they are properties of the script only.

It must be kept in mind that for centuries, the use of the rotunda “ꝛ” was conditioned by the environment. The expansion of abbreviations in the diplomatic transcription may alter this environment, further illustrating the need to replace the rotunda “ꝛ” with plain “r” in a diplomatic transcription. The rotunda “ꝛ” originated in the ligature “o” + “ʀ” (“oꝛ”); in Icelandic script, the rotunda “ꝛ” was then extended to the position immediately following other “round” letters, including “þ”, “b”, and “ꝺ”. One common occurrence of the rotunda “ꝛ” is in the abbreviated form of the pronominal form þeir, which in a facsimile transcription would be rendered as in the manuscript, “ꝥꝛ”, retaining both the rotunda “ꝛ” as well as the abbreviation. In a typical diplomatic transcription, on the other hand, the abbreviation would be expanded and the rotunda “ꝛ” rendered as plain “r”; that is, “þeir”. Once the abbreviation has been expanded, the rotunda “ꝛ” becomes inadmissible, many would argue, as no 13th- or 14th-century scribe would have used the rotunda “ꝛ” immediately following the letter “i”: “þeıꝛ”.

The distinction between “d”/“ꝺ” and “ð” reflects a phonological distinction between the dental stop and the dental fricative; consequently, it would be retained in a diplomatic transcription (as “d” vs. “ð”). The contrast between the round “s” and the long “ſ” in West Norse manuscripts sometimes reflects the phonological distinction between the geminate ss and the short s, respectively. Even if this is not always the case, many editors would retain it as a precautionary measure.

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| d ꝺ ð | d ð |

| e | e |

| f ꝼ | f |

| m | m |

| r ꝛ | r |

| s ſ | s ſ |

| t ꞇ | t |

| v ꝩ | v |

Diacritics – accent marks, dots and hooks – frequently have phonological value, but not always. They are often used to denote quantity (marking long vowels or consonants) or quality (different vowel qualities, such as ǫ vs. o). Sometimes they are, however, without phonological value, as, for example, when vowels that almost certainly were short are rendered with a superscript acute accent. Rather than attempting to differentiate accurately between diacritics with phonological value and those that are superfluous, it seems more practical to simply reproduce all diacritics in the diplomatic transcription (exactly as in the facsimile transcription). As an exception to this rule and in compliance with a long tradition in Norse editorial scholarship, the undotted “i” (that is, “ı”) is rendered with a dot in a diplomatic transcription, even if it is without a dot in the manuscript and the facsimile transcription. The contrast between “ı” and “í” in the manuscript (and the facsimile transcription) is thus replaced by the contrast “i” vs. “í” in the diplomatic edition. Similarly, “y” is usually rendered without the superscript dot (“ẏ”), as the principal function of the dot appears to have been to distinguish “y” from the Insular “ꝩ” (the two are otherwise practically identical in many hands).

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| á | á |

| a̋ | a̋ |

| ä | ä |

| í | í |

| v́ | v́ |

| ǫ | ǫ |

| ỏ | ỏ |

| ę | ę |

| ı | i |

| ẏ | y |

Note that diacritics – both superscript dots and superscript strokes (bars) – can serve as abbreviation symbols. A consonant symbol with a superscript dot or a superscript bar would typically denote a geminate (long) consonant. A “g” with a superscript dot or “n” with a superscript bar would thus be rendered as such in a facsimile transcription, “ġ” and “n̄”, but in a diplomatic edition the diacritics would be expanded resulting in “gg” and “nn”, respectively, as shown in the table below with some more examples.

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| ġ | gg |

| ṙ | rr |

| k̇ | kk |

| n̄ | nn |

| m̄ | mm |

Diacritics are thus treated in two different ways, as illustrated by the contrast between, on the one hand, a vowel symbol with a superscript accent or a superscript dot, such as “á” or “ȧ”, and, on the other hand, a consonant symbol with a superscript dot, such as “ġ”. In both cases, the diacritic serves to denote length, but the former is transcribed as is, while the latter is treated as an abbreviation and expanded in a diplomatic transcription, “á” or “ȧ” vs. “gg”.

Ligatures and fusions are also treated differently depending on whether they consist of vowel symbols or consonant symbols. Vowel ligatures are transcribed as such (and diacritics retained) in both a facsimile and a diplomatic transcription, as they could (potentially) signify a phonological contrast. This is not always the case, but rather than trying to determine if there actually is a contrast or not, these are best retained across the board, as shown with some examples in the table below.

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| ꜳ | ꜳ |

| | |

| æ | æ |

| ǽ | ǽ |

| ꜵ | ꜵ |

| | |

| ꜹ | ꜹ |

| | |

By contrast, consonant ligatures or fusions, are only optionally reproduced in a facsimile transcription and replaced by their individual components in the diplomatic transcription, as shown in the table below. In ch. 6.5.6, we recommend encoding consonant ligatures by the <seg> element with the @type="lig" attribute, e.g. <seg type="lig">bb</seg>. The <seg> element offers a convenient way of grouping characters or words, and will also be used in a somewhat different context in ch. 5.3.1 and ch. 5.3.2 below.

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| | af |

| | aꝼ |

| | ap |

| | ar |

| | bb |

| | gg |

| | oc |

| ſt | ſt |

Small capitals are frequently used in Icelandic manuscripts to denote geminate consonants; these are typically not treated as abbreviations, but transcribed as small capitals in both facsimile and diplomatic transcriptions. Small capitals may also appear with a superscript dot; for example, “ʀ̇”. These should not be treated mechanically interpreting the superscript dot as a signal of length, as that is almost certainly not what the scribe had in mind. In expanding abbreviations, the role of the editor is to expand in such a way as the scribe himself would have spelled the word had he decided to write it out in full. It seems highly improbable that treating “ʀ̇” as “ʀʀ” (or perhaps “rrrr”?!) would be consistent with the scribe’s intention. Instead, small capitals with a superscript dot should be transcribed as such both in a facsimile and a diplomatic transcription.

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| ɢ | ɢ |

| ɴ | ɴ |

| ʀ | ʀ |

| ɢ̇ | ɢ̇ |

| ʀ̇ | ʀ̇ |

As mentioned above, this is not a fixed standard, but rather guidelines that can be adapted to different projects. The editorial policy can be described in the header.

For East Nordic, there is an exception and an addition which should be addressed:

| Facsimile level | Diplomatic level |

|---|---|

| r ꝛ ʀ | r |

| ʉ | ʉ |

To the best of our knowledge, there is no phonological distinction between the three

allographs “r”, “ꝛ” and “ʀ” in East Nordic, so we suggest that they are

all rendered by the character “r” on the diplomatic level. Also in Old Norwegian, the

small capital “ʀ” is usually just an ornamental variant of the ordinary “r”,

such as in “Maʀia” (for Maria, not Marria), but there are some examples of the Icelandic geminate usage, so we

suggest that the distinction between “r” and “ʀ” is kept for Old Norwegian. The

final character, the barred “ʉ” is frequently found in Old Danish manuscripts. It has

often been rendered with “y”, possibly because it is lacking in many typefaces.

However, since it is now part of the official Unicode Standard at 0289, we believe

it should be kept at the diplomatic level (although it might be rendered as “y” on

the normalised level).

As an example of a typical diplomatic transcription, let us return to the short passage from the Old Icelandic manuscript, AM 233 a fol (in ill. 4.1 above):

In this transcription, expansions are set out by the element <ex> and in the display usually by italics. The text would then be transcribed as

d<ex>ro</ex>ttin<ex>n</ex> vá&rscapdot; baud michaele hof<ex>ud</ex> engli.

at fylg<ex>ia</ex>. adam ok &aolig;llu<ex>m</ex> helgu<ex>m</ex> h<ex>an</ex>s

at leida þa i p<ex>ar</ex>adi&slong;um hína fornu.and displayed as

drottinn

vá baud michaele hofud engli. at fylgia adam ok ꜵllum

helgum hans at leıda þa i paradiſum hína

fornu.

In what is often called semi-diplomatic editions, such as the majority in the series Editiones Arnamagnæanæ (København 1958–), abbreviations are expanded silently, i.e., without the use of italics. In electronic editions, this decision can be left to the stylesheet. As long as the information is kept in the <ex> element a display with italics can easily be restored.

4.4 The normalised level

The normalisation of the orthography is intended to further enhance the readability of the text. Medieval orthography is not as consistent as modern orthography and typically varies from one scribe to another, from one period to another, and, moreover, within the work of the same scribe. While removing this variation can inevitably result in the loss of some information, it will yield a much more readable text.

There is no single standard for normalising Old Norse texts. Icelandic texts are frequently normalised to conform to the Icelandic language around or shortly after 1200; this is the standard used by series such as Íslenzk fornrit. For Old Norwegian, Gammelnorsk ordboksverk (The Old Norwegian Dictionary), applied a slightly different standard. Yet other standards have been used for Old Danish and Old Swedish.

See further on normalised orthography in ch. 10.

As an example of an Icelandic text normalised according to the standard used in the Íslenzk fornrit series, we can once more return to the passage from AM 233 a fol. (ill. 4.1) which would be rendered as

Dróttinn várr bauð Michaele h&oogon;fuðengli at fylgja Adam ok &oogon;llum

helgum hans at leiða þá í paradísum hina fornu.and displayed as

Dróttinn várr bauð Michaele hǫfuðengli at fylgja Adam

ok ǫllum

helgum hans at leiða þá í paradísum hina

fornu.

Note that at this level all characters have been encoded using official Unicode code

points. So rather than encoding the character “ð” with the entity

“ð” it has been encoded simply as “ð”, using its code point in

Latin-1 Supplement, 00F0. The only exception here is the “o ogonek”, which for

practical purposes has been encoded with the entity “&oogon;”, even if this

character, too, has a Unicode code point, 01EB in Latin Extended-B. A suitable

keyboard layout is helpful for the actual typing of some of these characters, but in

general, all Medieval Nordic texts can be encoded without resorting to entities as

long as the text is rendered on a normalised level. Many Old Swedish and Old Danish

texts can also be encoded with a minimal amount of character entities.

4.5 Single-level transcriptions

While this handbook contains a number of examples of texts that have been transcribed on two or three levels, i.e. what we refer to as multi-level transcriptions, it should be emphasised that a text may be transcribed on a single level and be fully Menota compatible. This is indeed the default case for printed editions. For an archive such as Menota, the most frequent level is the diplomatic one, as described in ch. 4.3 above. For example, all texts stemming from Gammelnorsk Ordboksverk are single-level transcriptions on the diplomatic level.

| Elements | Contents |

|---|---|

| <w> | Contains a word. |

| <pc> | Contains a punctuation mark. |

| <me:facs> | Contains a reading on the facsimile level. |

| <me:dipl> | Contains a reading on the diplomatic level. |

| <me:norm> | Contains a reading on the normalised level. |

The table above list the most important elements in a single-level transcription. First of all, each word should be encoded in a <w> element and each punctuation mark in a <pc> element. As explained in ch. 5.3 below, the <w> element simplifies the encoding of words written apart or together, the position of line beginnings and hyphens, and, perhaps of greatest importance, it makes the transcribed text ready for any kind of grammatical annotation. In addition to these two elements, the level of transcription should be specified by one of the elements <me:facs>, <me:dipl> or <me:norm>.

Note: The “me” prefix can only be used with a RELAX NG schema. It must be left out in texts which will be validated against a DTD.

Ill. 4.2. From the translation of Alcuin’s De virtutibus et vitiis in the Old Norwegian Homily Book, the section on grið, ‘peace’. AM 619 4to, f. 2v, l. 15–21.

The following example from the Old Norwegian Homily Book in ill. 4.2 above renders the text on a diplomatic level. It is a single-level encoding, and since it is on the diplomatic level, we would refer to it as a single-level encoding on the diplomatic level.

<pb ed="ms" n="2v"/>

. . .

<lb ed="ms" n="15"/>

<w><me:dipl>GRøðare</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>hæims</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>þa</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>er</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>h<ex>ann</ex></me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>stæig</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>upp</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>til</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>faður</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>sins</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>í</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>hi<ex>m</ex>na</me:dipl></w>

<lb ed="ms" n="16"/>

<w><me:dipl>þa</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>gaf</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>h<ex>ann</ex></me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>lǽre svæinu<ex>m</ex></me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>sinu<ex>m</ex></me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>boðorð</me:dipl></w>

<w><me:dipl>friðar</me:dipl></w>

. . .Single-level transcriptions may also be on the facsimile level, as illustrated in the transcription below. In this case, it is not fundamentally different from the diplomatic level, since many Old Norwegian manuscripts have rather few abbreviations. We note, however, that the round “s” has been rendered with the long “s” of the source, and that the abbreviation marks are rendered in <am> elements, while they were expanded in <ex> elements in the diplomatic transcription.

<pb ed="ms" n="2v"/>

. . .

<lb ed="ms" n="15"/>

<w><me:facs>GRøðare</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>hæimſ</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>þa</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>er</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>h<am>&bar;</am></me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>ſtæig</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>upp</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>til</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>faður</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>ſinſ</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>í</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>hi<am>&bar;</am>na</me:facs></w>

<lb ed="ms" n="16"/>

<w><me:facs>þa</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>gaf</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>h<am>&bar;</am></me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>lǽre ſvæinu<am>&bar;</am></me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>ſinu<am>&bar;</am></me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>boðorð</me:facs></w>

<w><me:facs>friðar</me:facs></w>

. . .A single-level transcription may contain the normalised level only, but this is rare. A normalisation is usually not done directly from the source, but by way of a diplomatic rendering. However, keeping to the normalised level only may be useful for the encoding of an existing, normalised version of a text, as long as this keeps closely to the document structure of the source.

<pb ed="ms" n="2v"/>

. . .

<lb ed="ms" n="15"/>

<w><me:norm>Grǿðari</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>heims</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>þá</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>er</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>hann</w></me:norm>

<w><me:norm>steig</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>upp</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>til</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>fǫður</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>síns</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>í</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>himna</me:norm></w>

<lb ed="ms" n="16"/>

<w><me:norm>þá</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>gaf</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>hann</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>lǽrisveinum</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>sínum</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>boðorð</me:norm></w>

<w><me:norm>friðar</me:norm></w>

. . .As discussed in ch. 10.3 below and exemplified in ch. 10.4.2, this normalisation of the orthography follows the rules of the Ordbog over det norrøne prosasprog.

4.6 Multi-level transcriptions

Multi-level transcriptions allow the transcriber to render various aspects of the text in one or more specific levels. While the facsimile level can be seen as an “as is” level, rendering the text in the source with as little interpretation as possible, the two next levels, the diplomatic and normalised levels, allow for specifications of the transcriber’s perspective and interpretation of the text.

The levels of a multi-level transcription should be grouped in a <choice> element, and this element comes in addition to those discussed above for single-level transcriptions.

| Element | Contents |

|---|---|

| <choice> | Groups alternative readings, such as <me:facs>, <me:dipl> and <me:norm>. |

In the following, we shall discuss some of the options for a multi-level transcription. As will be seen, having several levels at disposal allow for a more detailed and distributed encoding, so that some elements may be used on one level and other elements on complimentary levels.

4.6.1 Editorial intervention

Editorial intervention is sometimes required to produce a readable text – or, in some cases, a text which can be annotated for syntax or information structure. Corrections of scribal errors, the insertion of individual letters, words or even phrases (accidentally) omitted by the scribe, conjectures about illegible words, or insertion of punctuation may be called for to enhance the quality of the text. The level of editorial intervention will, of course, depend on the aims of the transcription and the needs of the intended readership. This will also depend on the number of levels transcribed. Typically, the facsimile transcription is free of any such intervention; after all, faithfulness to the manuscript is the hallmark of the facsimile transcription. Any such editorial intervention is, therefore, best left to the diplomatic or normalised level. The division between the two may vary somewhat. In the absence of a normalised transcription, the diplomatic level would be the appropriate place for the editor to step in and emend the text for the benefit of the reader. By the same token, the normalised level would be best suited for this in a transcription with both diplomatic and normalised level. The facsimile transcription and the normalised transcription are, as if it were, at the opposite ends of the spectrum of editorial intervention, where the facsimile transcription allows only minimal intervention while the normalised level is produced by maximising the role of the editor.

The question of editorial intervention will be discussed in more detail in ch. 9.3 below, giving a number of examples of single-level and multi-level transcriptions. Although a single-level transcription can be made on either of the three levels discussed here, it is as a rule done on the diplomatic level.

4.6.2 Special characters

In a transcription on all three levels – facsimile, diplomatic, and normalised – the transcription of any given word can be different at the three levels, as shown with some examples below. In “leɢıa”, the undotted “ı” is replaced by dotted “i” at the diplomatic level, but the small capital “ɢ” is retained as it has phonological value. In the normalised orthography, the geminate g is spelled with the digraph “gg” and the “i” is replaced by “j”. In “ſıðan”, the long “ſ” is retained at the diplomatic level but replaced by “s” in the normalised orthography. The undotted “ı” is replaced by dotted “i” at the diplomatic level, but in the normalised orthography it is rendered with an acute accent, “í”, in order to represent a long vowel. In “gıỏꝼ”, the undotted “ı” and the Insular “ꝼ” are replaced by dotted “i” and Caroline “f”, respectively, at the diplomatic level, while the “ỏ” remains. In the normalised orthography, “i” and “ỏ” are replaced by “j” and “ǫ”, respectively.

In the three tables below, transcriptions and renderings are illustrated with images from the Icelandic law manuscript GKS 3270 4to (ca. 1340–1360).

| Facsimile | Transcriptions | Renderings |

|---|---|---|

| <me:facs>le&gscap;ıa</me:facs> <me:dipl>le&gscap;ia</me:dipl> <me:norm>leggja</me:norm> | leɢıa leɢia leggja |

| <me:facs>&slong;ıðan</me:facs> <me:dipl>&slong;iðan</me:dipl> <me:norm>síðan</me:norm> | ſıðan ſiðan síðan |

| <me:facs>gı&ocurl;&fins;</me:facs> <me:dipl>gi&ocurl;f</me:dipl> <me:norm>gjǫf</me:norm> | gıỏꝼ giỏf gjǫf |

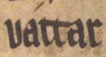

The facsimile transcription is the most detailed one and often requires the transcription of palaeographic detail that is not retained at neither the diplomatic level nor in a normalised version. Since the degree of palaeographic detail is significantly reduced at the diplomatic level, it sometimes is identical with the normalised level. Consequently, the facsimile transcription often is different from the two other transcriptions, as shown below. In “henꝺꝛ”, the Uncial “ꝺ” and the rotunda “ꝛ” are retained only at the facsimile level, but replaced with the standard “d” and “r” at the diplomatic level. In “haꝼðı”, the Insular “ꝼ” and the undotted “ı” are reproduced at the facsimile level only, but replaced with standard “f” and “i” at the diplomatic level. In “váꞇꞇar”, the flat-topped “ꞇ” only belongs to the facsimile transcription, but is replaced by standard “t” at the other levels.

| Facsimile | Transcriptions | Renderings |

|---|---|---|

| <me:facs>hen&drot;&rrot;</me:facs> <me:dipl>hendr</me:dipl> <me:norm>hendr</me:norm> | hendꝛ hendr hendr |

| <me:facs>ha&fins;ðı</me:facs> <me:dipl>haꝼðı</me:dipl> <me:norm>hafði</me:norm> | haꝼðı hafði hafði |

| <me:facs>vá&trot;&trot;ar</me:facs> <me:dipl>váttar</me:dipl> <me:norm>váttar</me:norm> | váꞇꞇar váttar váttar |

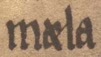

Occasionally, all three levels are identical:

| Facsimile | Transcriptions | Renderings |

|---|---|---|

| <me:facs>er</me:facs> <me:dipl>er</me:dipl> <me:norm>er</me:norm> | er er er |

| <me:facs>mæla</me:facs> <me:dipl>mæla</me:dipl> <me:norm>mæla</me:norm> | mæla mæla mæla |

| <me:facs>kona</me:facs> <me:dipl>kona</me:dipl> <me:norm>kona</me:norm> | kona kona kona |

If the text is normalised according to the rules of ONP, however, the verb mæla would be spelt with an accent over the vowel, “mǽla” (cf. ch. 10.3.1.4 below).

4.6.3 Structural properties

Page beginnings (<pb/>), column beginnings (<cb/>), and line beginnings (<lb/>) sometimes occur in the middle of a word. As these structural properties can be relevant at all three levels of transcription, it is recommended that they be indicated at all levels (repeated in all three transcriptions of the word). A break that occurs between words, falls outside the <w> element, and needs not to be repeated. See ch. 3 for an inventory of structural encoding.

4.6.4 Punctuation

In the facsimile transcription, the punctuation of the manuscript is accurately reproduced. The normalised transcription (or the diplomatic transcription, if there is no normalised transcription) may need different punctuation or the insertion of punctuation marks missing at the facsimile level. In such cases, the punctuation in the <pc> element will only be inserted in the <me:norm> level. See ch. 5.4 for more details on the encoding of punctuation.

4.6.5 A sample encoding of a three-level transcription

In a three-level transcription, the elements are the same as in a single-level transcription. The main difference is that the levels are encoded so that up to three text strings co-exist within the boundaries of the <w> elements. In order to make this sctructure fully transparent, we recommend using the <choice> element for the grouping of the <me:facs>, <me:dipl> and <me:norm> elements.

As an example of the encoding of a three-level transcription, we can once more turn to the passage from AM 233 a fol in ill. 4.1 above. Here, we are using character entities to a higher degree than necessary (as discussed in ch. 4.2 above).

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>&drot;<am>&osup;</am>ttin<am>&bar;</am></me:facs>

<me:dipl>d<ex>ro</ex>ttin<ex>n</ex></me:dipl>

<me:norm>Dróttinn</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>vá&rscapdot;</me:facs>

<me:dipl>vá&rscapdot;</me:dipl>

<me:norm>várr</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>bau&drot;</me:facs>

<me:dipl>baud</me:dipl>

<me:norm>bauð</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>michaele</me:facs>

<me:dipl>michaele</me:dipl>

<me:norm>Michaele</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>ho&fins;<am>&dsup;</am> engli</me:facs>

<me:dipl>hof<ex>ud</ex> engli</me:dipl>

<me:norm>h&oogon;fuðengli</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<pc>

<choice>

<me:facs>.</me:facs>

<me:dipl>.</me:dipl>

<me:norm></me:norm>

</choice>

</pc>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>at</me:facs>

<me:dipl>at</me:dipl>

<me:norm>at</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>&fins;ylg<am>&ra;</am></me:facs>

<me:dipl>fylg<ex>ia</ex></me:dipl>

<me:norm>fylgja</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<pc>

<choice>

<me:facs>.</me:facs>

<me:dipl>.</me:dipl>

<me:norm></me:norm>

</choice>

</pc>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>a&drot;am</me:facs>

<me:dipl>adam</me:dipl>

<me:norm>Adam</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>ok</me:facs>

<me:dipl>ok</me:dipl>

<me:norm>ok</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>&aolig;llu<am>&bar;</am></me:facs>

<me:dipl>&aolig;llu<ex>m</ex></me:dipl>

<me:norm>&oogon;llum</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>helgu<am>&bar;</am></me:facs>

<me:dipl>helgu<ex>m</ex></me:dipl>

<me:norm>helgum</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>h<am>&bar;</am>s</me:facs>

<me:dipl>h<ex>an</ex>s</me:dipl>

<me:norm>hans</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>at</me:facs>

<me:dipl>at</me:dipl>

<me:norm>at</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>lei&drot;a</me:facs>

<me:dipl>leida</me:dipl>

<me:norm>leiða</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>þa</me:facs>

<me:dipl>þa</me:dipl>

<me:norm>þá</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>i</me:facs>

<me:dipl>i</me:dipl>

<me:norm>í</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs><am>&pbardes;</am>a&drot;i&slong;um</me:facs>

<me:dipl>p<ex>ar</ex>adi&slong;um</me:dipl>

<me:norm>paradísum</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>hína</me:facs>

<me:dipl>hína</me:dipl>

<me:norm>hina</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<w>

<choice>

<me:facs>&fins;ornu</me:facs>

<me:dipl>fornu</me:dipl>

<me:norm>fornu</me:norm>

</choice>

</w>

<pc>

<choice>

<me:facs>.</me:facs>

<me:dipl>.</me:dipl>

<me:norm>.</me:norm>

</choice>

</pc>The rather verbose encoding illustrated above becomes much more concise when displayed by a suitable stylesheet. Typically, the stylesheet will pick one of the levels for the display so that the text string becomes linear, as it is in the source.

4.6.5.1 Display of levels

The display of levels varies with the stylesheets being used, but probably all stylesheets will agree on the display of the characters as such.

Ill. 4.3. Niðrstigningar saga, an Old Norse translation of the apocryphal Evangelium Nicodemi. AM 233a fol, 28v, l. 1–2. This is identical to ill. 4.1 above, repeated here for the sake of convenience.

This is an approximate rendering of the display in the Menota archive of the text in ill. 4.3:

| Facsimile display |

|---|

| 1 ꝺ ͦꞇꞇın̄ vá bauꝺ mıchaele hoꝼᷘ englı. aꞇ ꝼylgᷓ aꝺam ok ꜵllū 2 helgū ħs at leıꝺa þa ı ꝑaꝺıſum hína ꝼornu. |

| Diplomatic display |

|---|

| 1 drottinn vá baud michaele hofud engli. at fylgia adam ok ꜵllum 2 helgum hans at leıda þa i paradiſum hína fornu. |

| Normalised display |

|---|

| 1 Dróttinn várr bauð Michaele hǫfuðengli at fylgja Adam ok ǫllum 2 helgum hans at leiða þá í paradísum hina fornu. |

For reasons of line alignment in the Menota archive, the stylesheet will present the text on all levels with line beginnings and line numbers. In other stylesheets, line beginnings will not be displayed on the diplomatic and the normalised levels. This applies to the stylesheets in app. F.3 below.

4.6.5.2 Focal levels

As stated above, the elements <me:facs>, <me:dipl> and <me:norm> are not defined in TEI, but are part of the namespace we have defined for Menota texts. Please see the schemas in app. D.

The three levels discussed here can be seen as focal in the sense that they are typical and frequently used levels of text representations in Medieval Nordic editions (as defined in Haugen 2004). Several additional levels can be added, e.g. a <me:pal> level for an even more detailed palaeographical encoding of the text. This level has been included in the Menota schemas, but is not seen as one of the focal levels.

Guðvarður Már Gunnlaugsson 2003 offers a more detailed typology of editorial levels in the Old Norse editorial tradition. For example, a level between the diplomatic and normalised, usually called “halvdiplomatrisk” (semi-diplomatic), is the standard level in many of the Arnmagnæan editions.