Ch. 10. Normalisation

Version 3.0 (12 December 2019)

by Haraldur Bernharðsson, Odd Einar Haugen and Ivar Berg

10.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses the normalisation of the orthography of (1) lemmata and (2) texts in Menota. A strict normalisation of the former is important for the consistency and searchability of the annotated texts in the corpus. This normalisation refers to the contents of the @lemma attribute described in ch. 11.2. The normalisation of texts can not be specified as strictly, partly because there are no commonly accepted normalisation rules for Old Danish and Old Swedish and partly because there are some variation also within the rules for Old Icelandic and Old Norwegian (Old Norse). This type of normalisation refers to the regularisation of texts within the <me:norm> element discussed in ch. 4.4 above.

10.2 Normalisation of lemmata

The orthography of lemmata should adhere strictly to established dictionaries in the field. For Old Icelandic and Old Norwegian, we strongly recommend using the orthography of ONP: Dictionary of Old Norse Prose as stated in ch. 11.2 below.

Some of the Old Norwegian texts in the archive have received lemmata in the orthographic norm of Gammelnorsk Ordboksverk described in ch. 10.3.1.3 below. This information should be kept, but preferably in a separate @me:orig-lemma attribute, which comes in addition to the ordinary @lemma attribute.

For Old Swedish and Old Danish, we have at the moment no strong recommendations, but refer to the standard dictionaries in the field. See also the links for these languages in ch. 15.4.2.3 and ch. 15.4.2.4 below, and the general discussion in Haugen 2019.

10.3 Normalisation of texts

Medieval (Norse) orthography is not as systematic as modern orthography. Typically, the medieval orthography varies from one scribe to another, from one period to another, and, moreover, within the work of the same scribe. This orthographic variation can detract significantly from the readability of the text. In order to make the text more accessible to the readers, the editor may choose to remove this orthographic variation and present the text in a normalised orthography.

The normalisation of a medieval text is, however, not an easy undertaking. The modern editor (obviously) lacks native fluency in both the Old Norse language and the linguistic standard he is imposing on the text (even if the latter is a modern creation).

At the outset, the editor will have to make two practical decisions: (1) Select the norm, and (2) decide the scope of the normalisation.

When it comes to selecting a norm, there are mainly two choices for an edition based on a single manuscript:

(a) Normalisation based on internal criteria. In this kind of normalisation, the language of the manuscript itself would be used as a point of reference. A manuscript from the middle of the 14th century would thus retain (as far as possible) its mid-14th-century characteristics in a normalised edition. This can be a challenging task and not many editions have used normalisation of this sort.

(b) Normalisation based on external criteria. Typically, this requires imposing on the manuscript text an orthographic and linguistic norm from a different period. There are, for example, two main alternatives under this heading when editing Icelandic texts: (i) Classical Old Icelandic normalised orthography, based on the Icelandic language around or shortly after 1200 (on which see more below), and (ii) Modern Icelandic normalised orthography.

The fundamental aim of normalised orthography is to remove orthographic variation that detracts from the readability of the text. In practice, however, the normalisation usually affects different aspects of the language. The orthographic manifestation of sound changes is erased or inserted, morphological forms are altered and sometimes even the word order is changed. The outcome is, therefore, not only an edition with a normalised orthography, but rather with normalised language, and the editor must decide how extensive a normalisation is needed for his intended readership.

10.3.1 Normalisation of Old Norse texts

The orthography of Old Norse texts can be normalised in several ways. The ten selected words in table 10.1 highlight variation between standard dictionaries and text editions. While the overall variation is less than the table might lead one to believe, there is obviously necessary to make a number of minor decisions for the normalisation of Old Norse.

| ÍF | ONP | Baetke | Norr Ordb | GNO | Fritzner | Mod Ice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hræðask | hrǽðask | hræðask | hræðast | ræðast | hræðast | hræðast |

| sœkja | sǿkja | sœkja | sǿkja | sœkia | sœkja | sækja |

| jǫrð | jǫrð | jǫrð | jǫrð | iorð | jörð | jörð |

| eyzla | eyzla | eyðsla | eyðsla | øyðsla | eyzla | eyðsla |

| gæzla | gǽzla | gæzla | gæzla | gæzla | gæzla | gæsla |

| snilld | snilld | snild | snild | snild | snild | snilld |

| tǫlðu | tǫlðu | tǫldu | tǫldu | toldu | töldu | töldu |

| sœmð | sǿmð | sœmd | sǿmd | sœmd | sœmd | sæmd |

| ólǫg | ólǫg | ólǫg | úlǫg | úlog | úlög | ólög |

| hjálp | hjǫlp | hjálp | hjǫlp | hiolp | hjölp | hjálp |

Table 10.1 Normalisation in dictionaries and text editions of Old Norse. ÍF = Íslenzk fornrit; ONP = Ordbog over det norrøne prosasprog; Baetke = Walter Baetke, Wörterbuch zur altnordischen Prosaliteratur; Norr Ordb = Norrøn ordbok; GNO = Gammelnorsk Ordboksverk; Fritzner = Johan Fritzner, Ordbog over Det gamle norske Sprog; Mod Ice = Modern Icelandic. This table was originally set up by Robert K. Paulsen.

In this chapter, we will discuss four particularly relevant norms, (1) the orthographic normalisation in 18th and 19th century editions, based on the contemporaneous Icelandic orthography, (2) the Íslenzk fornrit norm, (3) the Old Norwegian norm of Gammelnorsk Ordboksverk in Oslo, and (4) the norm of the Dictionary of Old Norse Prose in Copenhagen.

10.3.1.1 Normalisation in 18th and 19th century editions

When medieval scribes copied manuscripts, they mostly followed their own orthography and also frequently modified the text in other ways, and this practice continued as long as manuscripts were being copied by hand. A conscious attempt to reproduce the original text letter by letter only arose in scholarly treatment of the old manuscripts during the early modern era (e.g. Árni Magnússon’s apographa, accurate copies of charters). The idea that one should employ a consistent orthography is connected to the emergence of printing. However, the first printed Old Norse texts in the late seventeenth century (by Olof Verelius and his successors in Sweden, Peder Hansen Resen in Denmark, and Þórður Þorláksson in Iceland) continued the manuscript tradition by printing the manuscript at hand rather uncritically and with contemporary Icelandic spelling (Finnur Jónsson 1918, pp. 25–30.

The editions by Det kongelige nordiske Oldskriftselskab, founded 1825 by C.C. Rafn and Rasmus Rask, marks a new practice (the following is based on Ivar Berg 2014, where more examples and a more thorough discussion can be found). The editions normalised the spelling, although not very strictly; “u” and “o” are for instance both used in endings, and each volume also pays some attention to the manuscript on which it is based. Some orthographic principles were carried out, like “k” where the manuscript varied between “c” and “k”, and a consistent distinction between the vowel “i” and the semivowel “j”. The normalisation was based on Rask’s ideas, as they were presented in his grammars, and to a large degree based on modern Icelandic practice (and pronunciation). There are two main reasons for this: One was Rask’s ideas of a shared orthography for Old and Modern Icelandic, which for instance made him use “â” for former /aː/ which had changed to /oː/, e.g. “vân” for Old Icelandic ván, Modern Icelandic von. Another reason was a faulty understanding of diachronic change in Icelandic, and as historical linguistics made advances the orthography of Old Norse editions was changed to reflect the language of the “Golden age” in the High Middle Ages (cf. Wollin 2000).

Konráð Gíslason was one of those who contributed to the improved understanding of Old Norse as different from Modern Icelandic, especially through his Um frumparta íslenzkrar túngu í fornöld (1846) and later in various articles. In the synthetic and fully normalised edition of Hrafnkels saga freysgoða (1839), which Konráð published together with P.G. Thorsen, it was explicitly stated that the orthography was supposed to represent the Stand der Forschung.

The first thorough grammar (with an accompanying reader) after Rask’s works was published by P.A. Munch and C.R. Unger in 1847. In some regards they followed Jakob Grimm more than Rask, nevertheless, whether e.g. “á” was said to represent /aː/ or /aw/ did not matter for the normalisation, which was in any case “á”. Munch and Unger did among other things differ between “æ” and “œ”, and their ideas were followed in their own edition of Fagrskinna (1847) and their and Rudolf Keyser’s edition of Konungs skuggsjá (1848). The aim of the normalisation was the romantic idea of the language in its “best period”. On the other hand, Barlaams ok Josaphats saga (1851) by Keyser and Unger was normalised according to the Old Norwegian language of the main manuscript (Holm perg 6 fol.), also where lacunas had to be filled from Icelandic manuscripts and one page even translated from Latin. Later Norwegian editions (mainly by Unger) usually followed the manuscript closely, and from Gustav Storm in the late nineteenth century an even stricter diplomatic tradition has dominated Norwegian editions (Haugen 1994, p. 154).

Building on the founding work of Rask and the further elaborations by especially Konráð Gíslason and the Danish linguist K.J. Lyngby as well as his own studies of the primary sources, Ludvig Wimmer published a new grammar in 1870 (revised Swedish edition 1874) with an accompanying reader; the reader was subsequently revised in several new editions and its normalisation proved to be very influential. Whereas the first edition followed the “usual” normalisation, Wimmer wrote an introduction to the second edition (1877) where he discussed the issue systematically. The aim for normalisation is the language in its classical state, identified as the thirteenth century, and the Icelandic Book of homilies is especially important, not least because of its consistent marking of vowel length, a notoriously difficult matter because of many subsequent changes. (The praise of the Book of homilies was echoed by Adolf Noreen in his grammar (1st ed. 1884, 4th ed. 1923)). To reach this classical linguistic state Wimmer replaced some younger forms in the first edition with older ones, e.g. preterite forms of reduplicating verbs like hljópu for younger hlupu and accusative plural of masculine u-stems like sonu for younger syni. The historical approach is evident: The norm is supposed to reflect the oldest known language.

Wimmer’s normalisation has largely been accepted, e.g. in the most widely used editions today, the Íslenzk fornrit series. However, Adolf Noreen criticised it as being unsuitable for a historical phonology, and preferred a more archaic orthography, for instance distinguishing between á and . This represents a point where historical linguistics deviated too much from accustomed spellings to be accepted in text editions, and very few follow this norm. Another point is that editors following Noreen would remove Old Norse from Modern Icelandic. Even though Rask’s goal of a shared normalisation for the old and the modern language has been abandoned, the differences are not disturbingly large for the Icelandic readership. A point worth mentioning in this context is the use in most normalised editions of double consonants before inflection endings, as in the preterite forms kenndi and byggði (inf. kenna and byggja) as in modern Icelandic. The editions e.g. in Altnordisches Saga-Bibliothek follow the Mainland Scandinavian practice of shortening the consonants in this position, cf. Norwegian kjende and bygde (inf. kjenna and byggja).

Many nineteenth century editions, including the first edition of Wimmer’s reader, points to the “usual” normalisation in text editions, and Berg 2014 claims that the normalisation is thus a result of practice and tradition more than conscious decisions. Nonetheless, the basis is often found in the “best” manuscripts from the thirteenth century, identified as the “classical” period.

10.3.1.2 Icelandic

As already indicated, there are mainly two alternatives when selecting an external standard for presenting a text in Icelandic:

(i) Classical Old Icelandic normalised orthography takes as its point of reference the Icelandic language around or shortly after 1200. This is the standard used by Ludvig F.A. Wimmer in his Oldnordisk læsebog (2nd ed. 1877) referred to above and it has since then been widely used with some minor modifications, in for example the series Altnordisches Saga-Bibliothek and Íslenzk fornrit. This has also been used for the normalisation of lemmata by Ordbog for det nordiske prosasprog (ONP). The following are some of the characteristics of the classical Old Icelandic normalised orthography:

1. Orthographic distinction of the short vowels ǫ : ø

2. Orthographic distinction of the long vowels ǽ : ǿ

3. Orthographic distinction of vowels i : y, í : ý, and ei : ey

4. Etymological vá rendered “vá”: svá, hvárt, vápn

5. Etymological long monophthong é rendered “é”: mér, sér, þér

6. Etymological short monophthong e rendered “e” before ng: lengi

7. Word-final -t in unstressed position: at, þat, hvat

8. Word-final -k in unstressed position: ok, ek, mik

9. The middle voice exponent as -sk: kallask

10. Orthographic distinction of the endings -r and -ur (no epenthetic u): nom. sing. armr : nom.-acc. plur. sǫgur

The editors of the Íslenzk fornrit series, have in some instances employed a slightly younger variant of this standard for 14th-century texts, by, for instance, adopting the vowel mergers ǫ + ø > ö and ǽ + ǿ > æ.

(ii) Modern Icelandic normalised orthography is often used in text editions in Iceland. This requires a fair amount of modernising. The following are some of the characteristics of the Modern Icelandic normalised orthography vis-à-vis the classical Old Icelandic orthography:

1. The merger of the short vowels ǫ + ø > ö

2. The merger of the long vowels ǽ + ǿ > æ

3. Orthographic distinction of vowels i : y, í : ý, and ei : ey

4. Etymological vá rendered “vo”: svo, hvort, vopn

5. Etymological long monophthong é rendered “é”: mér, sér, þér

6. Etymological short monophthong e rendered “e” before ng: lengi

7. Fricativisation of word-final -t in unstressed position: að, það, hvað

8. Fricativisation of word-final -k in unstressed position: og, eg, mik

9. The middle voice exponent as -st: kallast

10. No orthographic distinction of the endings -r and -ur (epenthetic u): nom. sing. armur : nom.-acc. plur. sögur

In addition, the Modern Icelandic normalisation sometimes incorporates morphological changes, especially in the endings of the verbs.

10.3.1.3 Old Norwegian

Gammelnorsk ordboksverk (The Old Norwegian Dictionary) was established in 1940 with the aim of publishing a dictionary of the Old Norwegian language. For this work, a fixed orthography was needed for the dictionary entries (lemmata), which should correspond to the then established norm for Old Icelandic, but also take into consideration the specific traits of Old Norwegian. The most recent version of these rules is available here in extenso:

For a broad, historical survey of Gammelnorsk ordboksverk, see Magnus Rindal 1991.

The major differences between the GNO norm and the Íslenzk fornrit norm are the following (cf. pp. 8–9 of the rules):

1. The long vowels á, é, í, ó, ú and ý were indicated by accents, “á”, “é”, “í”, “ó”, “ú” and “ý”. However, the long ǽ was rendered as “æ” without accent, presumably because a short æ was not recognised in this orthography. The long ǿ was rendered by the ligature “œ”, and the short ø by “ø”. In charters (diplomer) dated after 1300, the long ǿ should be indicated by an accent, “ǿ”.

2. The vowel ǫ (in Modern Norwegian referred to as “o med kvist”) was rendered by “o”, i.e. no distinction was made between o and ǫ.

3. The consonant symbols were the ordinary ones. There was only one symbol for each of the consonants r, s, f and v (not the round “ꝛ”, the tall “ſ” nor the Insular forms “ꝼ” and “ꝩ”). The combination “ck” was rendered “kk”.

4. The falling diphthongs were rendered “ei”, “au” and “øy”.

5. The rising diphthongs were rendered “ia”, “io” (not with “j”), similarly “-ia” and “-iu” in word-final position (e.g. “skilia”, “kirkiu”).

6. The consonant h was left out in front of l, n and r (e.g. “lutr” m., “nakki” m. and “ringr” m.).

7. The privative prefix was ú (e.g. “úvinr” m., “úreinn” adj.).

8. The unstressed vowels were rendered as “i” (for i and e) and “u” (for u and o), similarly for “-liga” and “-ligr”. In other words, there was no indication of vowel harmony in the orthography.

9. Reflexive verbs had the ending “-st” (“nálgast” etc.).

10. The consonant combination ft/pt was rendered by “pt” (“eptir” prep.).

11. The consonant combination fn/mn was rendered by “fn” (“sofna” vb.). However, there might be exceptions to this rule, especially for words which were closely connected to another word of the same root, e.g. “samna” vb. (cf. “samr” adj.).

12. There was no indication of u mutation (“u-omlyd”) in unstressed positions, hence “prédikarum” rather than “prédikurum”, “kunnastu” rather than “kunnustu”, etc. In editorial comments, however, mutated vowels might be used in this position, e.g. “kolluðum” rather than “kallaðum”.

10.3.1.4 The Dictionary of Old Norse Prose (ONP)

The orthographic norm of ONP is described in these general terms on their web pages:

ONP’s orthographic norm is a reconstruction of the state of Old Norse (medieval Icelandic/Norwegian) ca. 1200–1250 (closer to 1200 than 1250).

Where a choice between an Icelandic and a Norwegian standard is necessary, the more conservative of the two, most often the Icelandic, is chosen. But where the Norwegian form is the more conservative (e.g. in the case of non-lengthening of vowels before certain consonant groups), the Norwegian is selected.

Non-assimilated foreign words (labelled ‘alien.’) are presented in their native spelling, based as far as possible on the orthography of standard dictionaries of the relevant language. Classical Latin is chosen in preference to medieval.

The more integrated loanwords are adapted to the Old Norse norm and are treated on a par with the indigenous vocabulary.

ONP’s orthographic norm aligns closely with the traditional norm, as it has developed over the years in normalised text editions (e.g. Íslenzk fornrit), in dictionaries (e.g. Heggstad, Hødnebø & Simensen: Norrøn ordbok, 1975), and in other handbooks (reference will be made below to Noreen: Altisländische und altnorwegische Grammatik, 4. ed., 1923, and Larsson: Ordförrådet i de älsta islänska handskrifterna, 1891).

The most noticeable deviation from normal practice in editions and dictionaries is the choice of the graphs ǽ and ǿ for the long æ- and ø- phonemes (in harmony with Noreen’s grammar and standard linguistic usage). The choice of ǽ and ǿ (rather than æ and œ) was made partly with a view to the spelling of the manuscripts but mainly on the basis of practical and pedagogical considerations: as a result there is an acute accent over all long vowels in normalised text and unfortunate confusion between æ and œ (esp. in italics) can be avoided.

The orthographic variation which the sources themselves demonstrate arises partly because the texts cover a span of approx. 400 years during which major linguistic changes emerge, partly because of the regional variation, and partly because of the non-standardised spelling of the individual manuscripts.

The orthographic norm which is used in headwords and other normalised text in ONP is therefore an abstraction that is not found in its full extent in any of the single manuscripts which consti tute ONP’s corpus. Especially normalisation of headwords in their grammatically cardinal forms sometimes entails the construction of forms the existence of which is not recorded in the available data.

Normalisation of Old Norse texts removes them from their chronological and regional context and blurs their individuality, but standardisation can bring the literature closer to its readers. When, for example, a medieval text is presented in a Modern Icelandic guise, a bridge is formed to the Icelandic reader. Similarly, standard Old Norse normalisation gives students from all over the world a means by which to approach the texts with the help of dictionaries, grammars and other reference tools. In order to provide this shared and open access this dictionary normalises its headwords and Old Norse phraseology. The citations themselves, however, are retained as far as possible in their unnormalised form; in the edited articles they are presented in a manner that is as close to that of the surviving text as the manuscripts and the editions allow.

(ONP’s normalisation forms the backbone of the standard recommended by Menota = Medieval Nordic Text Archive // Arkiv for nordiske middelaldertekster, www.menota.org).

A detailed overview of the norm is given on the ONP website referred to above.

Please note that this link may change.

10.4 Samples

This section illustrates various types of normalisation of texts in Old Icelandic and Old Norwegian.

10.4.1 Old Icelandic

The sample below is from AM 133 fol., Kálfalækjarbók, dated to around 1350, containing Njáls saga. The excerpt is from leaf 8v with the opening of chapter 10. Examples of two types of normalization are presented. On the one hand, the Classical Old Icelandic normalization as used by, for instance, the Íslenzk fornrit series. On the other hand, Modern Icelandic normalization. Instances where the latter differs from the Classical Old Icelandic normalization are highlighted in blue.

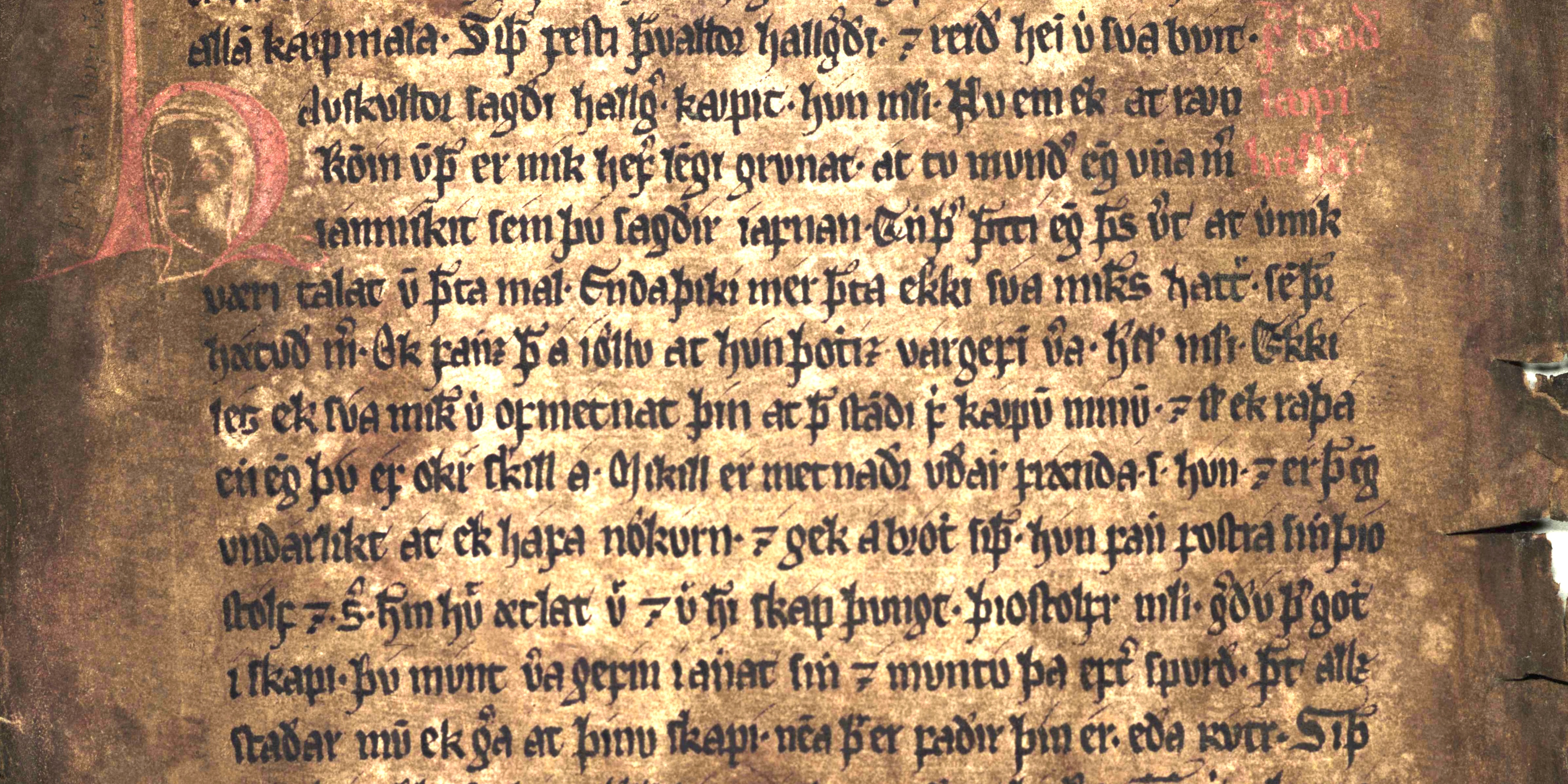

Ill. 10.1. The beginning of ch. 10 of Njáls saga. AM 133 fol, Kálfalækjarbók, f. 8v, l. 7–17.

10.4.1.1 Diplomatic transcription

The rubric at the end of the three first lines is displayed in red colour.

. . . fra brvð

havſkvlldr ſagði hallgerði kꜹpít. hn mǽlti. Nv em ek at rn lꜹpi

komín vmþat er mík hefir lengi grvnat. át tv mvndir eigi vnna mer hallgerðar

iánmíkít ſém þ ſagðír íafnan. Enn þer þottí eigi þes vert at viðmík

væri talat vm þetta mál. Endaþikí mér þetta ekki

ſa mikils hattar.

ſem þer

hǽtvð mer. Ok fannz þat á íllv

at hn þottíz várgefin

vera. hoſkvlldr mǽlti. Ekkí

leɢ ek ſa mikit við ofmétnat þín at þat ſtandi fyrir kpvm mínvm. ok ſkal ek

raþá

enn eigi þ éf okŕ ſkill á. Mikill ér metnaðr

vðarr frǽnda ſegir

hn. ok ér þat eigi

vndarlikt at ek háfa nkrn. ok gek ábrótt ſiþan. hn fann foſtrá

ſinn þíó

ſtólf ok segir honvm hvat ætlat var

ok var henni ſkáp þvngt. þioſtolfr mælti. gerð þer gott

í ſkapi.

þ mnt vera gefín í annat ſinn

ok mvnt þa eftir

ſpvrð. þviat allz

ſtaðar mvn ek gera at þínv ſkapí. nema þar er faðir þín ér. eða

ʀtr. Siþan

10.4.1.2 Classical Old Icelandic normalized orthography (Íslenzk fornrit style)

Frá brúðkaupi Hallgerðar

Hǫskuldr sagði Hallgerði kaupit. Hon mælti: „Nú em ek at raun

komin um þat,

er mik hefir lengi grunat, at þú myndir eigi unna mér

jafnmikit sem þú

sagðir jafnan. En þér þótti eigi þess vert, at við mik

væri talat um þetta

mál, enda þykki mér þetta ekki svá mikils háttar sem þér

hétuð mér;“ — ok

fannsk þat á í ǫllu, at hon þóttisk vargefin vera. Hǫskuldr mælti: „Ekki

legg ek svá mikit við ofmetnað þinn, at þat standi fyrir kaupum mínum, ok

skal ek ráða,

en eigi þú, ef okkr skilr á.“ „Mikill er metnaðr yðarr

frænda,“ segir hon, „ok er þat eigi

undarligt, at ek hafa nǫkkurn;“ — ok

gekk á brott síðan. Hon fann fóstra sinn, Þjós·

tólf, ok segir honum, hvat

ætlat var, ok var henni skapþungt. Þjóstólfr mælti: „Gerðu þér gott

í skapi.

Þú munt vera gefin í annat sinn, ok muntu þá eftir spurð, því at alls

staðar

mun ek gera at þínu skapi, nema þar er faðir þinn er eða Hrútr.“ Síðan . . .

10.4.1.3 Modern Icelandic normalized orthography

Frá brúðkaupi Hallgerðar

Höskuldur sagði Hallgerði kaupið. Hún mælti: „Nú er

ég

að raun

komin um það, er mig

hefur lengi grunað, að þú myndir eigi unna mér

jafnmikið sem þú

sagðir jafnan. En þér þótti eigi þess vert, að við mig

væri talað um þetta mál, enda

þykir mér þetta ekki svo mikils

háttar sem þér

hétuð mér;“ — og

fannst

það á í öllu, að

hún

þóttist vargefin vera. Höskuldur

mælti: „Ekki

legg ég

svo

mikið við ofmetnað þinn, að

það standi fyrir kaupum mínum, og

skal ég ráða,

en eigi þú, ef okkur

skilur á.“ „Mikill er metnaður

yðar frænda,“ segir hún, „og er það eigi

undarlegt, að

ég

hafi

nokkurn;“ — og gekk á brott síðan.

Hún fann fóstra sinn, Þjós·

tólf, og segir honum, hvað

ætlað var, og var henni skapþungt.

Þjóstólfur mælti: „Gerðu þér gott

í skapi. Þú munt

vera gefin í annað sinn, og muntu þá

eftir spurð, því að alls

staðar mun ég gera að þínu skapi, nema þar er faðir þinn

er eða Hrútur.“ Síðan . . .

10.4.2 Old Norwegian

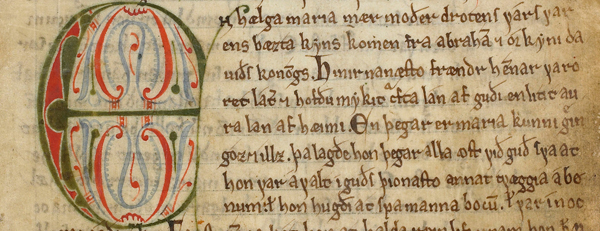

The sample below is from the earliest preserved Norwegian codex, AM 619 4to, which has been dated to ca. 1200–1225. Only about 8 fragments from the period ca. 1150–1200 are older. In the two normalisations exemplified below, words that differ are highlighted in blue.

Ill. 10.2 The opening of a homily on the Virgin Mary in The Old Norwegian Homily Book. AM 619 4to, f. 63r, l. 13–20.

10.4.2.1 Diplomatic transcription

En hælga maria mær moðer drotens várs var

ens bæzta kyns komen fra

abraham

ok ór kyni da·

uiðs konongs. Hinir nanæsto frændr hennar

varo

ret láter ok hofðu mykit crafta lán af guði en litit au·

ra lan af

hæimi. En þegar er maria kunni grein

góz ok íllz. þa lagðe hon þegar alla ꜵst við guð sva

at

hon var ávalt í guðs þionasto annat tvæggia á bø·

num. eða hon hugði at spamanna bocum. eða var í noc[coro]

10.4.2.2 Normalised text according to the GNO rules

En helga Maria mær móðir dróttins várs var

ins

bezta kyns komin frá Abraham ok ór kyni Da·

viðs konungs. Hinir nánæstu frændr hennar váru

réttlátir ok hofðu mikit krafta lán af guði en lítit au·

ra

lán af heimi. En þegar er Maria kunni grein

góz ok ills, þá lagði

hon þegar alla ást við Guð, svá at

hon var ávalt í Guðs þiónastu annat tveggia á bœ·

num, eða hon hugði at spámanna bókum, eða

var í nok[kuru]

10.4.2.3 Normalised text according to the ONP rules

En helga Maria mǽr móðir dróttins várs var

ins

bezta kyns komin frá Abraham ok ór kyni Da·

viðs konungs. Hinir nánǽstu frǽndr hennar váru

réttlátir ok hǫfðu mikit krafta lán af guði en lítit au·

ra

lán af heimi. En þegar er Maria kunni grein

góz ok ills, þá lagði

hon þegar alla ást við Guð, svá at

hon var ávalt í Guðs þjónustu annat tveggja á bǿ·

num, eða hon hugði at spámanna bókum, eða

var í nǫk[kuru]